Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries are one of the most common knee injuries in the United States – approximately 400,000 ACL injuries occur every year. Historically, orthopedic surgeons have had limited options in treating a torn ACL. In ACL reconstruction, today’s standard of care, the surgeon completely removes the remaining torn ACL and reconstructs it with either a tendon from the patient’s own leg (called an autograft) or a deceased donor (called an allograft).

Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) injuries are one of the most common knee injuries in the United States – approximately 400,000 ACL injuries occur every year. Historically, orthopedic surgeons have had limited options in treating a torn ACL. In ACL reconstruction, today’s standard of care, the surgeon completely removes the remaining torn ACL and reconstructs it with either a tendon from the patient’s own leg (called an autograft) or a deceased donor (called an allograft).

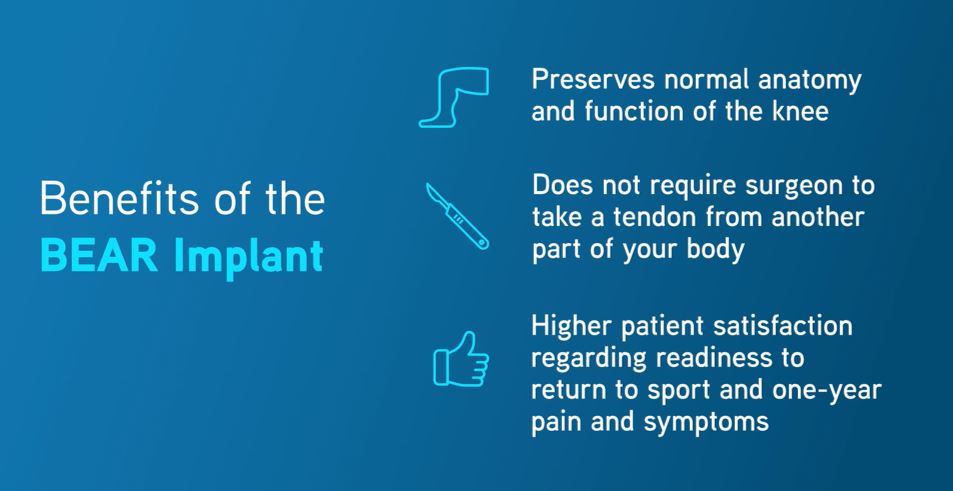

At Advanced Orthopedic Sports Medicine Institute (AOSMI), we are now offering a new technology called the BEAR® (Bridge-Enhanced ACL Restoration) Implant. The BEAR Implant is the first medical advancement granted approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that enables the body to heal its own torn ACL. This new approach is a paradigm shift from ACL reconstruction and is the first innovation in ACL tear treatment in more than 30 years.

AOSMI completed the first official procedure on November 15, 2022. Michael J. Greller, MD, MBA, CPE, FAAOS, a Board-Certified Orthopedic Surgeon who is Fellowship-trained in Sports Medicine led the procedure. He was assisted by Garret L. Sobol, MD, Board-Certified Orthopedic Surgeon who is also Fellowship-trained in Sports Medicine.

“There are a number of advantages to restoring a ligament instead of replacing it, and the BEAR Implant is an exciting medical technology that is the first to clinically demonstrate that it enables healing of the patient’s torn ACL while maintaining the natural knee anatomy,” said Dr. Greller “Encouraging clinical studies have shown faster recovery of muscle strength and higher patient satisfaction with regard to readiness to return to sport than traditional ACL reconstruction – the standard of care today.”

ACL Injuries – An Overview

Your knee joint is formed by three bones: the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone), and patella (kneecap). The ACL (Anterior Cruciate Ligament) is one of the four main ligaments in the knee that helps to stabilize the joint. It is located in the center of the knee – it runs from the backside of the femur (thigh bone) to the front of the tibia (shin bone). The ACL is responsible for preventing the tibia from sliding out in front of the femur, and helping to control rotational movements of the knee.

The majority of ACL injuries are non-contact injuries – when athletes while running, rapidly change directions, stop or decelerate, or land from a jump without properly bending their knees. ACL injuries can also occur from direct contact to the knee joint. Most ACL injuries are complete tears, in which the ligament has been torn in half or pulled directly off the bone.

Patients usually report hearing and feeling a popping sensation during the injury. After the tear, patients experience pain with swelling, instability of the joint, loss of full range of motion, tenderness, and discomfort while walking.

ACL injury treatment is focused on preventing further knee instability and protecting the joint from further trauma. The two approaches to treatment are the non-surgical approach and the surgical approach. The approach is dependent on the extent of damage to the knee and the patient’s willingness to modify activity. Young and competitive athletes who want to return to activities that require aggressive jumping, cutting and pivoting or deceleration movements, and patients with meniscal tears usually pursue surgical reconstruction. Patients who have partial tears, do not have knee instability, and don’t partake in these “at-risk” movements can maintain their knee stability with physical therapy and rehabilitation alone. However, physical therapy is a core component of ACL treatment, surgical or non-surgical. For complete tears, surgery is usually recommended.

Standard ACL Reconstruction vs. BEAR Implant

ACL reconstruction surgery remains the gold standard of care. In this procedure, the surgeon takes tendon from the patient’s patellar tendon (patellar tendon autograft), hamstring tendon (hamstring tendon autograft), or from a human donor (allograft) to replace the torn ACL.

Unlike reconstruction, the BEAR Implant does not require a second surgical wound site to remove a healthy tendon from another part of the leg or the use of a donor tendon. The BEAR Implant acts as a bridge to help ends of the torn ACL heal together. The surgeon injects a small amount of the patient’s own blood into the implant and inserts it between the torn ends of the ACL in a minimally invasive procedure. The combination of the BEAR Implant and the patient’s blood enables the body to heal the torn ends of the ACL back together while maintaining the ACL’s original attachments to the femur and tibia. As the ACL heals, the BEAR Implant is reabsorbed by the body, within approximately eight weeks.

BEAR Implant – Clinical Evidence

Safety and effectiveness of the BEAR Implant is supported by clinical evidence. As shown in Murray et. al 2019, IKDC scores, a patient-completed tool which contains sections on knee symptoms, function, and sports activities, from the BEAR Implant procedure was similar to that of ACL reconstruction two years post-surgery. AP Laxity, which measures stability of the knee joint, is the same as ACL reconstruction two years post-surgery. The BEAR Implant provides statistically better hamstring strength at 6 and 12 months, with the trend sustained to 2 years. BEAR Implant patients were also more likely to experience fewer contralateral ACL tears (tears in the non-injured knee) at two years. MRI indicates that the BEAR implant facilitates healing of the native ACL so that its size, geometry, and tissue composition are more like native ACL tissue than autograft. 86 percent of BEAR patients returned to pivoting sports by one year.

Risks and Limitations of the BEAR Implant

Following the BEAR Implant, patients are directed to follow the BEAR Implant physical therapy program. The BEAR Implant has the same potential medical and surgical complications as other orthopedic surgical procedures, including ACL reconstruction. These include the risk of re-tear, infection, knee pain, meniscus injury and limited range of motion. The BEAR Implant is indicated for skeletally mature patients at least 14 years of age with a complete rupture of the ACL, as confirmed by MRI. Patients must have an ACL stump attached to the tibia to construct the repair. The BEAR device must be implanted within 50 days of injury.

If you meet these criteria, you may be a candidate for the BEAR Implant procedure. To learn more about the procedure, request an appointment. If you have questions about ACL tears or if you are experiencing knee pain, contact us. With offices across New Jersey, the physicians and staff of Advanced Orthopedic Sports Medicine Institute are committed to restoring your health so that you can get back to your active lifestyle as quickly and safely as possible. To learn more about how you can benefit from expert orthopedic treatment, call us (732.720.2555) or request an appointment today.